Rhino safaris

Rhinos

are relatively rare these days,

only found a few specialist locations

three extant species of rhinoceros

Rhinos are the second largest land mammal in both Africa and the Indian subcontinent.

Unfortunately these animals continue to be heavily poached for their horn, which is (incorrectly) believed to have medicinal properties in the Far East.

There are two separate species of rhino in Africa, the smaller and more aggressive black or hook-lipped rhinos and more docile white or square-lipped rhinos.

There is one rhino species in Asia, namely the Indian rhinos (also known as the greater one-horned rhino).

If you want to see rhinos on your safari, then we will need to plan accordingly, since they are only commonly seen in a few select areas.

Frequently asked questions

It’s one of the great injustices of nature that certain sectors of humanity have chosen to attach such a huge value to rhino horn.

Every mature rhino is now obliged to carry a USD 100,000 bounty on its head.

To make it worse, they happen to live in poor countries where the ‘real value’ of a single horn is more like USD 10M. Imagine the carnage if people walked around with that kind of cash on them.

Rhino horns are used in Chinese traditional medicine. Their beneficial properties have never been proved and are almost certainly nonsense. They are also used to carve decorative dagger handles in parts of the Middle East.

During the darkest days of poaching back in the 1980s, Africa experienced a 90% reduction in rhino numbers. After a massive worldwide conservation effort most sub-species were saved from extinction and numbers have recovered modestly since then.

In recent years, the slaughter seems to have picked up again and rhino populations are once again under great threat.

Many wildlife reserves which have served as refuges are now unable to provide sufficient security against highly organised gangs of armed poachers and rhinos have had to be relocated into a smaller number of higher security areas.

This resurgence of poaching is most likely connected to the surging influence of China on the continent, as well as increased demand from an emerging but poorly-educated middle class in the Far East.

The situation remains extremely serious.

ten million dollars on your nose

The great irony of all this rhino poaching is that these animals could easily be farmed for their horn.

Unlike elephant tusks, which are extended teeth, rhino horns are made out of keratin, similar to hair and toenails. They grow continuously through the life of the animal.

There are farmers in South Africa who are ready and willing to farm rhinos, everything is in place and ready to go.

The theory is that by flooding the market with lower cost horn, the demand for poached horn would be severely undermined and the poaching crisis would be averted.

Unfortunately this rather obvious solution is presently being blocked by the United Nations CITES worldwide ban on the trade in rhino horn, which does not allow for a differentiation between poached and farmed material.

This is despite the fact that it is relatively easy to insert genetic markers into farmed horn, to enable easy differentiation.

It would appear that dirty underhand politics is at work here, with various vested interests gaining advantage through nefarious means.

Whilst this political impasse remains, rhinos continue to be needlessly slaughtered and huge efforts are needed to protect those few animals that remain.

a ready-to-roll solution

The hook-lipped rhinoceros, also known as the black rhinoceros, is the smaller ‘sports-model’ sub-species compared with the much larger square-lipped rhinoceros.

They are faster, more alert, more solitary and more aggressive, making them much more of a challenge to approach, especially on foot.

Their protruding muzzle is designed for browsing rather than grazing, so they are most commonly found in areas where the primary food source is bushes and shrubs rather than grass, or on rocky terrain where the grass needs to be carefully pulled from between the stones.

Hook-lipped rhinos were previously the most numerous type in Africa, with an estimated population of around 750,000 back in the year 1900. Populations fell steadily through the 1900s due mainly to loss of habitat, followed by a sudden 96% collapse in numbers between 1970 and 1992 due to illegal poaching.

Massive efforts have been put into saving these creatures from extinction, with breeding programmes having been established in South Africa and with animals being released back to their former ranges in several countries.

Despite these efforts, black rhinos remain critically endangered and, if anything, their situation seems to be once again becoming slightly more precarious.

Southwestern hook-lipped rhinos

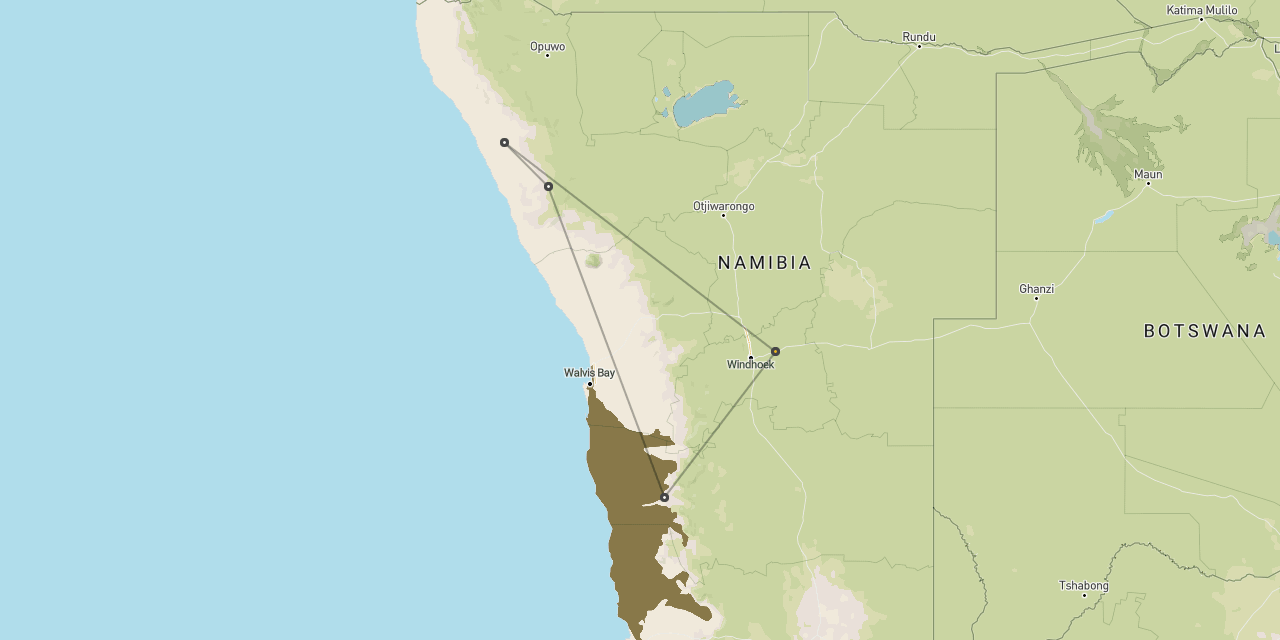

The Southwestern hook-lipped rhino is at home in the arid landscapes of Namibia, southern Angola and western Botswana. By far the best place to view them is on the wild and remote Palmwag Concession in Namibia Northwest, where the Save the Rhino Trust has been working for many years.

Guests at the wonderful Palmwag Rhino Camp and Hoanib Valley Camp are able to approach on foot, which can be an extremely exhilarating experience, as some of these rhinos are particularly skittish and seem ready to charge at the drop of a hat. Undoubtedly, this is amongst the best rhino interactions in Africa, these feisty creatures can get pretty lively.

The rhino population in this area, although naturally sparse, appears to be healthy. Although every time we go out with the wonderful rangers, we wonder how much longer the relatively poor local people can resist such a massive financial temptation.

Southcentral hook-lipped rhinos

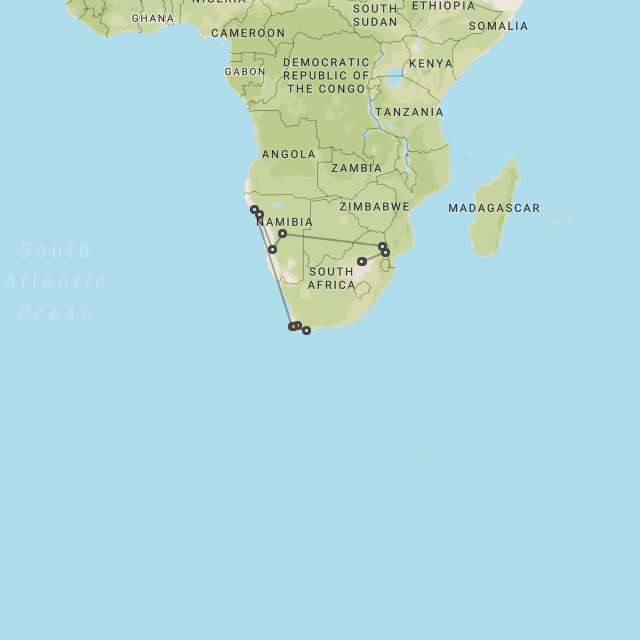

The Southcentral hook-lipped rhino previously had a home range which covered large parts of southern Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique and northern parts of South Africa.

By around 1990 these animals were virtually eliminated in the wild, but thankfully good numbers found protection in various fenced reserves, mainly in South Africa.

Since 2002 Southcentral hook-lipped rhinos have been reintroduced to various locations, most notably at Mombo Camp in the Okavango Delta area of Botswana and in the North Luangwa area of eastern Zambia.

During Covid, the dramatic drop in tourism saw a resurgence of rhino poaching and these projects were virtually returned back to square one. But efforts continue.

Eastern hook-lipped rhinos

The Eastern hook-lipped rhinos previously ranged across Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya and northern Tanzania.

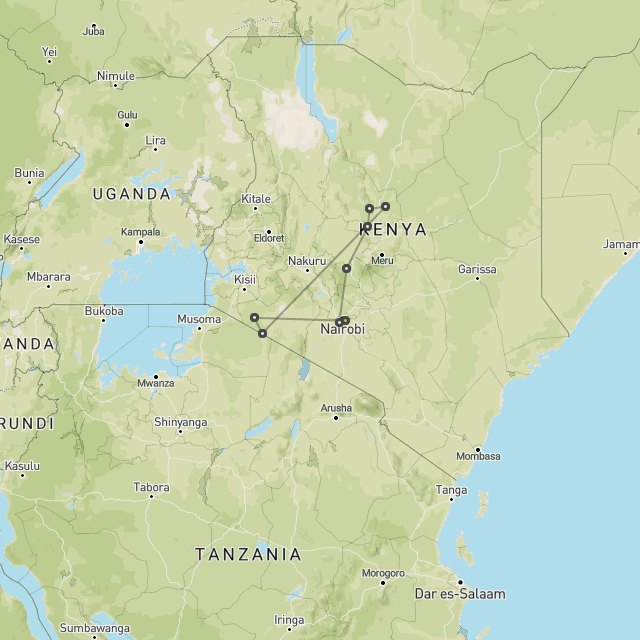

Today their numbers are very limited, with very modest free-roaming populations in Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti. The ones in the crater can be quite easy to find, whilst sightings in the Serengeti tend to be much more rare and precious. We have seen them for ourselves on several occasions, so we know where they hang out.

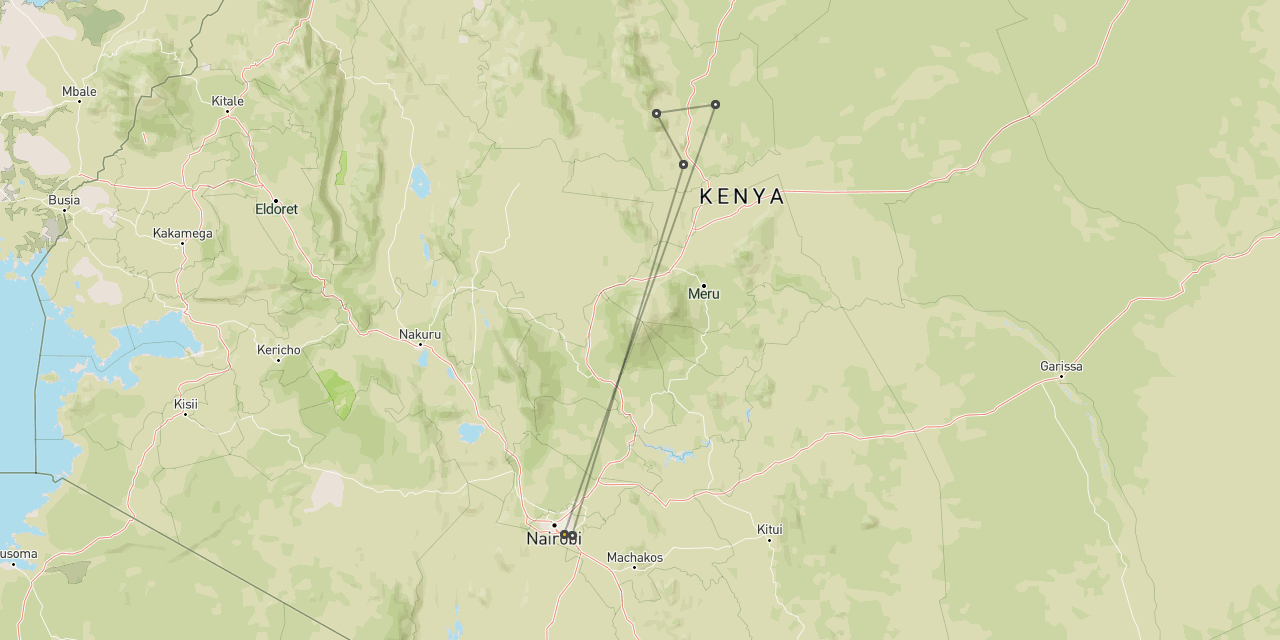

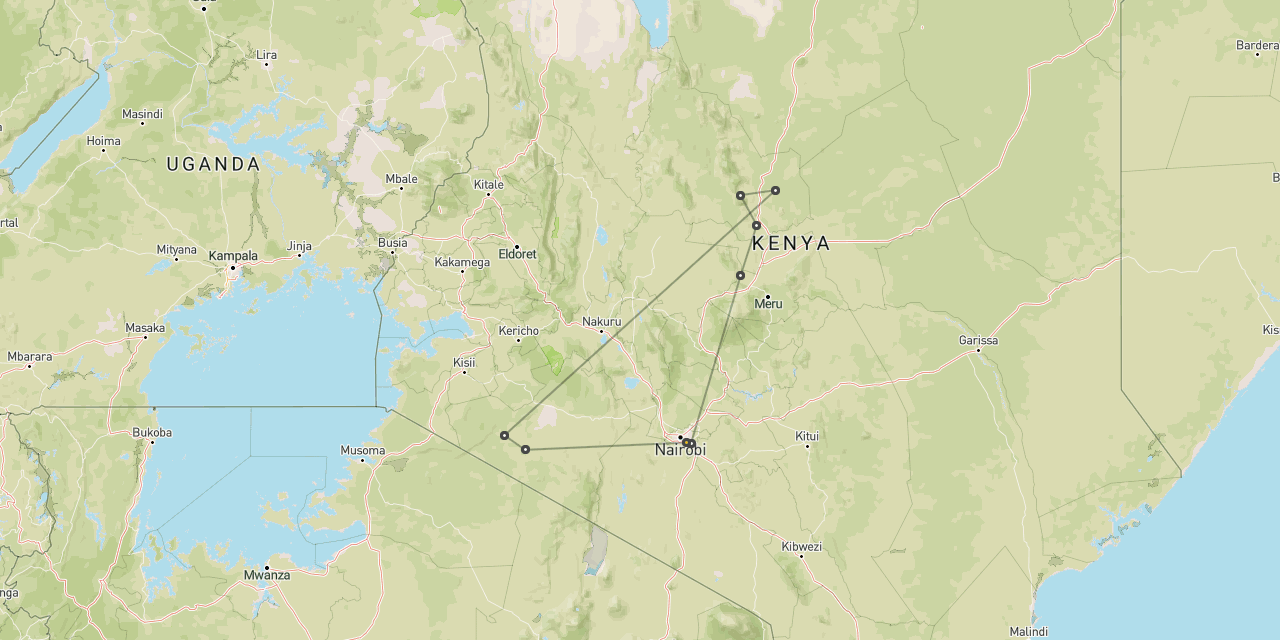

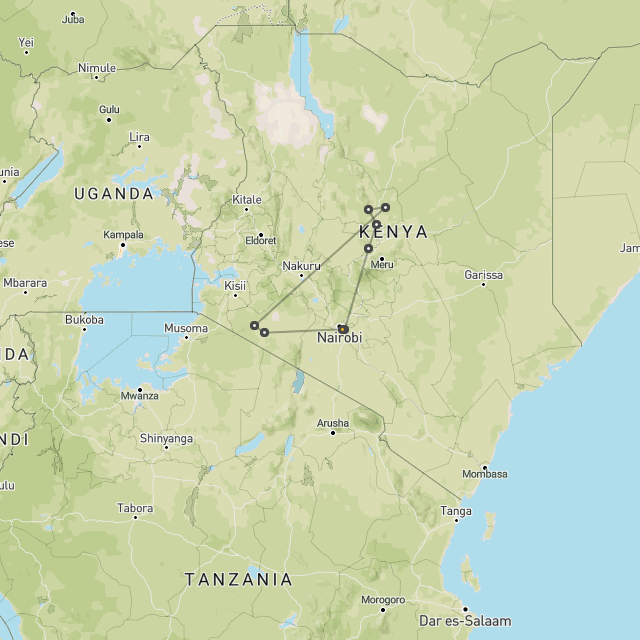

Captive populations exist in heavily guarded and fenced areas in the Maasai Mara, as well as at Ol Pejeta and Lewa Downs in the Laikipia South area of Kenya. All three locations can be visited and sightings are more-or-less guaranteed.

Perhaps the most important location for this subspecies is the rhino breeding and reintroduction programme run by Tony Fitzjohn on behalf of the George Adamson Wildlife Preservation Trust at Mkomazi in northeast Tanzania, a project which appears worthy of support, but which remains resolutely unapproachable.

Another really important location is Saruni Rhino Camp in northern Kenya, where a major release and protection scheme is underway and where they are much more accommodating to guests. In fact this is almost certainly our favourite rhino location in Eastern Africa.

West African hook-lipped rhinos

The West African hook-lipped rhino of Cameroon is thought to be extinct.

the feisty sports-model

The square-lipped rhinoceros, also known as the white rhinoceros, is considerably larger, more sociable and more docile than its hook-lipped cousins.

It is primarily designed for grazing, hence the broad shape of its muzzle and is therefore most commonly found in open grassland and savanna areas.

Southern square-lipped rhinos

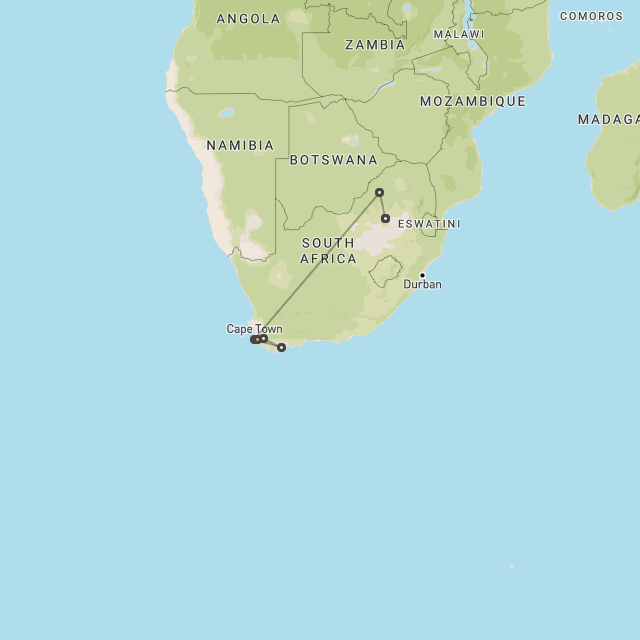

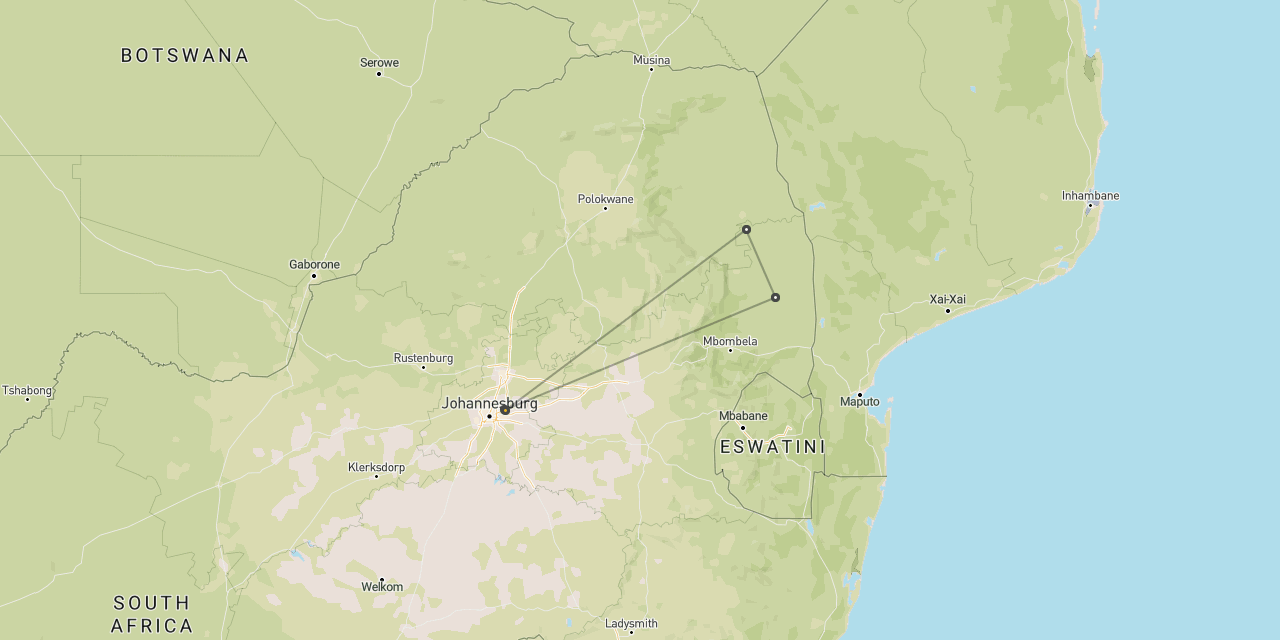

The Southern square-lipped rhino, which used to roam widely across South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, remains by far the most numerous of the two subspecies, with around 17,000 individuals thought to be living in the wild.

Over 90% of these are in South Africa, with Kruger, Madikwe, Phinda, Hluhluwe and other reserves all providing a decent chance of sightings.

Small numbers have also been reintroduced at Mombo Camp in the Okavango Delta area of Botswana and at Ongava Main Lodge in the Etosha area of Namibia, with both locations offering a reasonable chance of sightings.

Northern square-lipped rhinos

The Northern square-lipped rhino, which used to have a limited range in the border areas between Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Sudan and Uganda is now thought to be extinct in the wild, the last four remaining animals in the Congo’s Garamba National Park having last been sighted in 2006.

Again poaching is the problem, in this case largely by Somali bandits who believe that the horn has aphrodisiac properties.

Of the eight animals remaining in captivity, four were relocated from Dvur Kralove Zoo in the Czech Republic to the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in the Laikipia South area of central Kenya in December 2009 in the hope that they would start to breed.

Unfortunately, the last male died in 2018, but his sperm was frozen and scientists are hopeful that the subspecies can be recovered through artificial insemination, even if the recipient female may have to be a southern wide-lip.

Ol Pejeta is well set up to receive visitors, but is rather touristy.

larger and slightly more docile

Indian rhinos (also known as greater one-horned rhinos) are the second largest, after the African white rhino, reaching up to 186 cm (6’10”) at the shoulder and weighing up to 2200 kg (4850 lbs).

The most obvious characteristic is that they only have one horn, which tends to be much smaller than those of their African cousins. Their upper legs and shoulders are covered in bumps that make them look even more armour-plated than usual.

Their muzzles are somewhere in between the wide grass-grazing lips of the white rhino and the narrow tree-browsing lips of the black rhino, indicating that they are less specialist and able to handle a wider range of foliage.

The present home range of Indian rhinos runs in a swathe along the southern side of the Himalayas, from northern Pakistan, through northern India, southern Nepal, southern Bhutan, and northern Bangladesh.

The best location to view them is in Kaziranga National Park in the Assam region of northeast India, which is home to around 80% of an estimated total wild population of around 2500 animals.

pre-historic armour-plated behemoths

let us know about your specific interests

and we will help build an amazing safari

Extraordinary tailor-made adventures,

from earthy and edgy to easy and extravagant

From around USD 2500 per person, you set the ceiling

Sample Trips

Here are some of our popular trip shapes

Get started on your trip

It’s never too soon to get in touch, we are here to help with every stage of your planning.